August 24th, 2019 – Train Station, Ulaanbaator

I bought my train ticket yesterday, after the lady just announced that the train to Edernet was full: roll with it Chloé. One extra day in Ulaanbaator to hang out with Mongolian friends, use Internet while you have it, and do a last minute shopping trip. Turned out, I fried my laptop charger and was very glad to have a day to walk to “Computer Land” to find a brand new compatible laptop charger. Thanks to Globalization, I can even find Windows products in Mongolia – relief!

Train station. There is no turning back now. Folks looked at my strangely, some smiling curiously, a few bewildered as I wiggled my bike around trying to find my way to the damn “big” luggage room. There is no signs in English, I hold my train ticket written in cyrilic in one hand, almost as a weapon, to complement my gesticulations everytime I point at my loaded bike. I was so worried they would not accept my bike as it is that I had stomach aches throughout the afternoon. I wanted to avoid the hassle of putting my bike to pieces in a box and have it as formal checked luggage in the train, but my laziness certainly had the price of having to wait and hear the train officer’s verdict. I went to the awesome info kiosk where they have the only English word of the train station (and only English speaking staff): INFORMATION. Yes: that’s where I want to go. The lady is lovely and she laughs quietly when I asked if I could take my bike in the train nervously: she must have received three different calls from the Mongolian students I befriended during the program who helped me figure out how to get out of Ulaanbaator with my bike. It turned out to be too late to check in my bike – my heart fell into my chest: I messed up, and would have to catch the train tomorrow instead? “No”, the lady answered: I could simply bring it myself to the big heavy luggage wagon situated at the end of the train. So off I went, to find the end of the train, still a bit nervous that my bike would not be accepted given my late minute appearance.

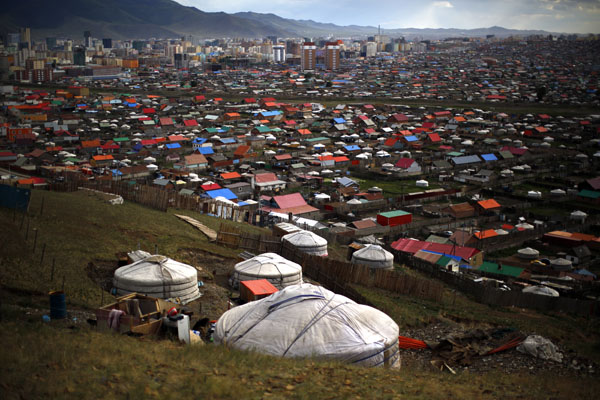

Once I got the the last wagon, I had to laugh at myself for being worried: how could I have ever worried about taking my bike on the train? Here I was, standing in the middle of piles of gigantic tractor tires, couches, ger furniture, and layers, layers of felt of gers. A bike would be the feather among the rest! I watched the train staff roll the big tires off the trolleys, and one after the other and bounce them from one’s arms to another’s arms to finally load them through the two wide-open metallic doors, their backs wet from the continued effort. Then it was the turn of furniture: the staff would disbalance one side of the couch, who laid like a king at the top of the neatly stacked pile of smaller items of furniture, and have it roll back towards the other side before giving it a one final good kick to have it slide off fully and down to the ground. What a team effort I was witnessing, there waiting patiently with my bike for it to be its turn. What I was also witnessing was symbolic of the ongoing and larger network of exchange between the city and the countryside of Mongolia, where goods available in the different regions are traded and moved between the two sites, often via relatives or acquaintances.

Night of August 24th, in the train to Erdenet, from Ulaanbaator

It smells like Kimchi Ramen Noodle soup everywhere and two or three bottles of Toe fruit juice – or at least sweet tea – lay open on middle tables. It makes me hungry even if I don’t cherish particularly Kimchi Ramen Noodles. Most recently, a lady walked with a whole transparent garbage bag filled with ramen noodle soup bowls ready to be devoured by hungry train passengers. There is really a whole job sector existing around selling things in the train, starting from card decks to full meals and packaged fruits. People enter and walk through the train at stations, announcing loudly what they are selling. You have to act quick if you want something, otherwise they are gone.

Train ambiance is actually quite nice. Some folks are playing cards; chatting pretty much does not stop throughout the evening; the lady’s phone under me keeps ringing as she tries to call someone without success (and now plays a game with music that I hear through her headphones); some are lightly snoring already; All of us are in a relatively long and slow journey in the train. While some will hop off throughout the night stops, you always wake up with a few of your neighbors who started at the same station than you. Once the main train station in Ulaanbaator is passed, the upper sleeping tables start squeaking open, often with the help of a friendly neighbor who helps you unpin it. That is when open and free spots go, and you have to work on getting that sleeping spot straight away: climb up the small feet steps on the sides of the sitting seats and duck down under the luggage compartment to crawl on the dark red fake leather sleeping table. From up there, you can actually stick your face in the window, and it feels pretty vibrant to have the Mongolian winds caress your skin as you stare endlessly in the landscape passing you. If you get lucky, you might get offered a cup of coffee from one of the train attendants, which makes the ride even more enjoyable… until you have to visit the train toilet (less enjoyable, especially that train toilets are closed 30 minutes before entering a city and 30 minutes after… a one hour waiting period for the coffee pressing your bladder).

August 25th 2019, in my tent, passed Bulgan. Writing after eating sourdough bread with raisins with German Mozzarella cheese that had been so long packaged and waiting in the supermarket that mold had grown under the sticker.

So tired from biking winds face.

August 28th, 2019 – Erhel Nuur, Alpine Lake

I am munching on cabbage and bready Mongolian cookies in my tent, as the last colors of the day faint outside. I just realized that I cracked my laptop screen and that it is no longer tactile. Damn it, I totally had forgotten that my laptop was in my backpack, and it has been shoved around quite a bit although I have no memory of when it could have been hit/fallen hard enough. It seems like it landed on a rock as the glass sheltered like a spider web starting from the side. Oh well, it sucks but at least it is in the corner of the screen, and I can still read without being bothered. I need to find a cushioned spot for it now, so not to worsen the damages – maybe it should hang out in my clothes dry bag.

There are a few jeeps and motorcycles that run near where my tent is, but it’s just a dirt track. It kinda makes me nervous in some ways to be here alone, while many families and that weird redded-eyes guy on the motorcycle know that I am here alone. All the sounds outside are amplified by my mind and imagination: it’s most likely all good, just a bit vulnerable. Mongolia has been very safe and friendly so far; the hospitality culture and “looking out” for each other is quite strong, even towards foreigners who cannot even communicate with them. Cars have been stopping, cellphone hooked to a relative who speaks English, to check if I need any kind of help when only, I had only been taking a post-lunch nap. I was offered water and rides as I went up a massive climb today, or have been invited multiple times, only though a show of hands, fed and invited to sleep in the family’s ger. Even if Mongolia is the least densely populated country in the world, it seems like there is always someone somewhere. The fact that there are barely any trees enhances this feeling of intimacy within the immensity: here, we can see all the way up to the next mountains, and similarly on the other side. You’ll pretty much always spot a ger in the far away distance: just keep your eyes out for a white spot, it might be 10-15 km away, but it will be there. It’s reassuring to have these visual Qs in the landscape. I have yet to have felt isolated or in a “remote” place: even on dirt roads with no road signs, there are folks who are passing by. So what is it about a low density country such as Mongolia then? Well, it is the very very low impact on nature caused by human, and the low amount of cityscapes. Here, telephone towers exist only in villages and the electric lines pretty much always follow roads. You can see in the far far away without encountering dense human settlements. And because of its generous grasslands and steppes, there are no trees to block sight.

I am so tired now. It’s 9:35 and my legs feel mummified in my toasty down sleeping bag. I am typing under my headlamp’s patient watch while on my right side my bags surely lay in a big mess.