Migration to Ulaanbaatar city has exponentially grown since the transition to democratization after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1990, as people were given freedom of movement, which was not the case under soviet centralized planning during which families were dispatched across different provinces in Mongolia.

Drivers of Migration

Expectations, structural circumstances (e.g. policies and institutions) and external circumstances tend to combine to become a reason to migrate. Overarching personal decision making and expectations are structural circumstances. These have to be stressed over personal decision making, as structural circumstances bind, facilitate or push people into personal decision making. The biggest drivers of migration from rural to urban sites in Mongolia include employment; educational opportunities; family obligations; health service access; shifting ways of life; economic reasons, including having loss one’s herd due to harsh winters (dzud). Families and relatives play an important role in decision-making when it comes to migrating, and often are supports in facilitating adaptation and providing information access. Moreover, the development focus in Mongolia is in Ulaanbaatar, centralizing and concentrating opportunities and resources in the capital rather than equitably distributing them around the country. For instance, there is none or only occasional help if herders lose their herds due to harsh winters, forcing them to integrate into the capitalist economy by moving to the city to sell their labor to a third party. Overall, there is a lack of policies and institutions to make structural equality and ensure the equitable distribution of resources across the country. The following life history illustrates the interplay between circumstances and expectations in migrant’s decision to move:

Zaya* was born in Uvs Province in a relatively underdeveloped infrastructure area and had poor access to education to services. The person knew little about the new destination, Darkhan, but had a sister and relatives living there, helping to access information. There was also market access to sell products. The herding lifestyle could be continued given the land accessibility outside Darkhan. The interviewee considered moving to Ulaanbaatar for educational opportunities but the limited access to information there was a barrier to a new migration. Yet, possible income in Ulaanbaatar would be uncertain and precarious. Moreover, herding in Ulaanbaatar is banned, requiring a shift in livelihood and uncertain or precarious income levels.

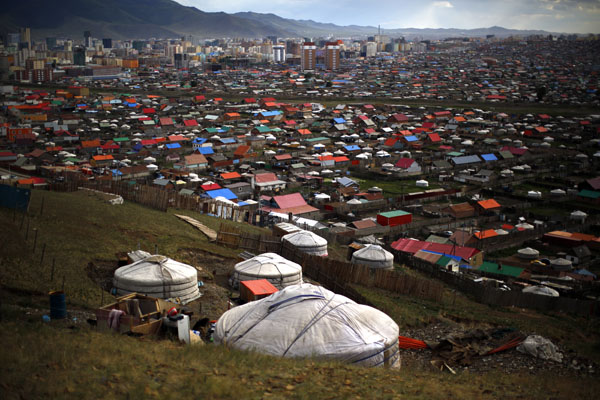

Ger Districts in Ulaanbaatar

Upon arrival, most migrants move in their ger and settle in the ger districts surrounding Ulaanbaatar, where 60% of the city’s population live. The ger districts use up 50% of the land in Ulaanbaatar, even if little urban planning goes into these areas. In average, migrants relocate three times before settling on their current place. There is no official registration when migrants choose a piece of land to settle on: they settle on inhabited land and after a few years, migrants are able to claim a land title. Until then, there is no legal safety net for the land, apart from the fact that all Mongolians are entitled to land under Mongolian constitution.

Ger districts present issues such as: health and security issues; polluted and neglected neighborhoods; and safety hazards in ger districts. Moving in an apartment building is seen as a symbol of social mobility and something people look forward to only if they come to have financial ease. Migrants come with expectations such as: economic opportunities, availability of employment, high salary and owning land. However, as they settle down, these expectations are not always met and migrants come to face multiple challenges, including lack of governmental support; contextual vulnerability; lack of information and difficultly registering. In accessing health care services for instance, there exists confusion and poor information as to where to go, how to register, and how to deal with bureaucracy in public medical center. People reported needing connections and paying bribes to access public hospital services. In finding employment, migrants struggle due to the lack of quality of employment; employer scam; age discrimination; or the lack of kindergarten access.

Since 2017, the city of Ulaanbaatar has banned new migrants to come to the capital in an effort to combat the urban sprawl, poor infrastructure and urban planning capacity, and air pollution. Drawing from a community assessment on migrant vulnerability published by Public Lab Mongolia, the ban on migration in Ulaanbaatar has increased the vulnerability of unregistered migrants living in Ulaanbaatar’s ger. While this ban is in place and migration figures have dropped, some people failed to register before the officialization of the ban or have settled after the ban was put in place. D Status of migrants in Ulaanbaatar often described in the available literature by the following key words: vulnerability; social exclusion; multi-dimensionally poor; limited service accessibility. Vulnerability is exacerbated in the case of unregistered migrants as service access and land ownership in Ulaanbaatar is limited and conditional to the registration status of migrants.s Experience of Migration